Experiences of co-creating survey with communities facing climate health risks

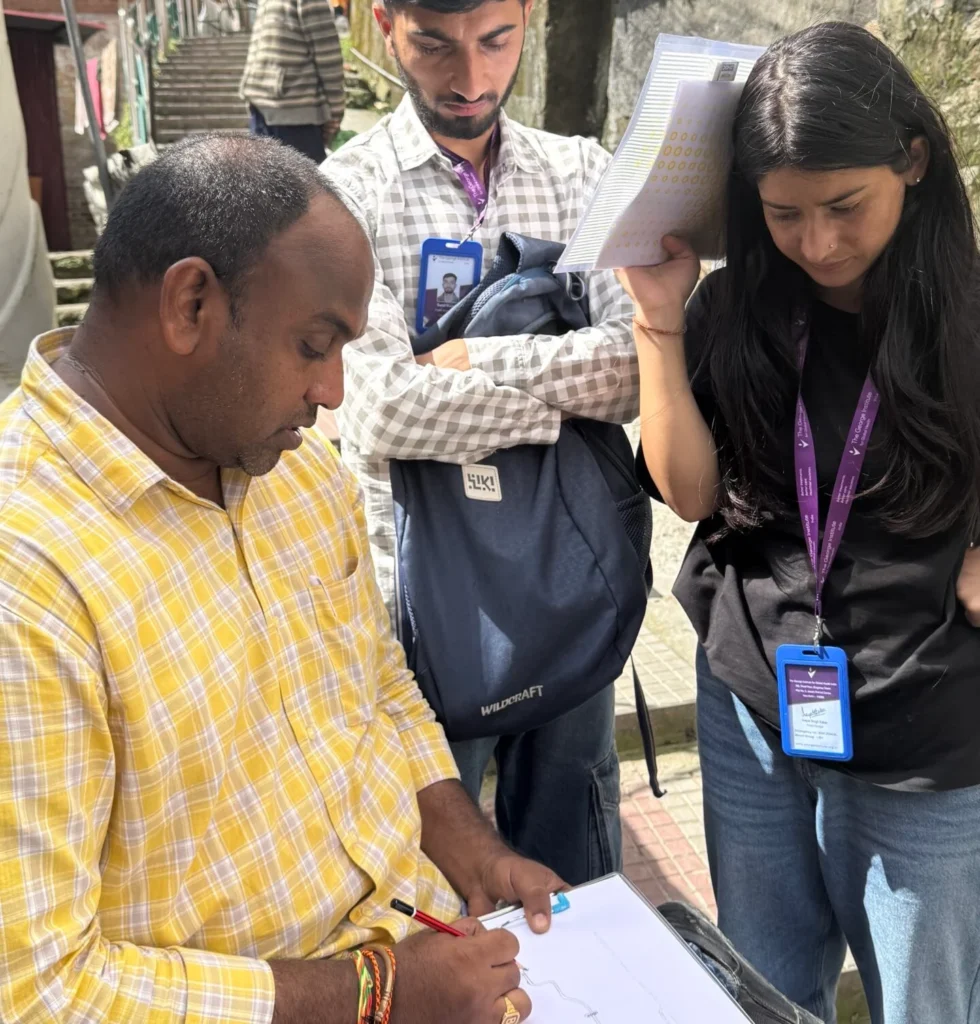

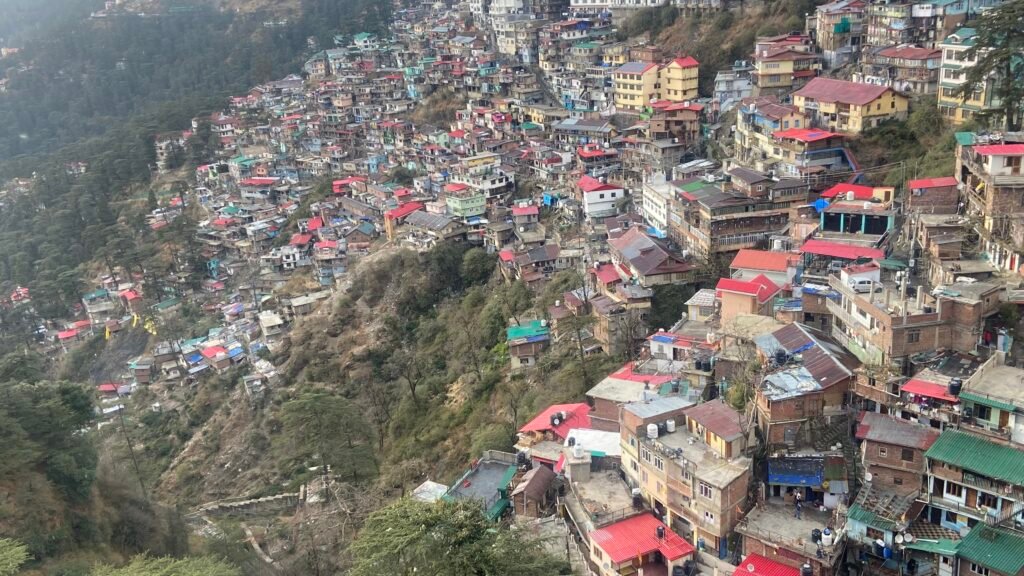

Experiences of co-creating survey with communities facing climate health risks In late October 2025, the Urban SHADE project in India will start on data collection related to the household level survey in the informal settlements in Shimla in Himachal Pradesh, Vijayawada and Guntur in Andhra Pradesh. The household survey aims to understand health impacts and vulnerabilities of people living in informal settlements, as well as the extent of care available to them in public health facilities during and following extreme weather events. The Urban Shade Project, aims to strengthen health services for people living in urban informal settlements, to respond to impacts of extreme weather events. The enumerators in both states underwent an extensive training programme in September, which covered the details about the project, ethics of data collection, mapping and use of survey software. The project has involved the community in every step of the way. The design of the survey tool – Household Survey: Social and Health Vulnerability Assessment related to Extreme Weather Events– was led by a member of the research team, Malini Aisola with extensive inputs from research and field team members. The survey includes social demographic profiles of household members, access to utilities and infrastructure, access to health services, housing, past impact of extreme weather events, people’s perceptions, awareness and responses on extreme weather events. The survey will be conducted in informal settlements in Vijaywada-Guntur, and two informal settlements in Shimla. The two extreme weather events we are looking at in the project are extreme heat and extreme rainfall/flooding.Through the household survey, the team aims to generate context-specific data about a variety of indicators of social and health vulnerability, and provide insights about how they shape experiences of extreme weather events. For example, those living in the poor quality houses, and do informal work may feel the impact of extreme heat more.The survey would enable granular descriptions at the settlement-level of prevailing conditions that could inform government policies and local preparedness planning including provision of health services. Consulting the community on survey tool The Urban SHADE research teams had fortunately worked with some of the settlement sites in the project earlier in another project called Accountability for Informal Urban Equity (ARISE), an action research project focussing on health and wellbeing of sanitation workers. In some other communities, efforts were made to engage with the community in a meaningful way before data collection. In Eidgah colony, a public meeting was organised with support from key stakeholders including the Maulvi of the mosque, the ward councillor, community leaders, an official from National Health Mission and ASHA workers in the settlement. Anmol Somanchi, a developmental economist and member of the research team in an advisory capacity, helped the team develop a conceptual framework for measuring vulnerabilities. After developing a basic draft with inputs from research and field team members, our team presented it to the members and stakeholders of the settlements in Vijayawada, Guntur and Shimla. The workshops included residents, community leaders, elected officials, health workers, civil society members of these settlements we are studying in including Krishna Nagar, and Eidgah colony in Shimla, Vambay colony and New Raja Rajeswari Peta (also called RR Peta) in Vijaywada, and Sarada colony in Guntur. The one-day workshop was organised by the research team of Inayat Singh Kakar and Yetika Dolker in Shimla, and Pavani Pendyala and Hemanth Chandu in Vijayawada in May. Apart from talking about the survey, key questions were read out and displayed in the workshop to the community members to discuss their relevance, the way they are worded, as well how the data could be relevant to the community for advocacy. Community members gave suggestions on improving the questions as options to click to elicit an appropriate answer. Mahesh aka Shiva who lives in RR Peta gave suggestions to simplify the Telugu questions, making it closer to spoken language rather than very Sanskritised. “In the workshop, you (Urban SHADE team) asked us whether we were able to understand the language or not, and modified the questionnaire based on the language we were able to understand,” said Mahesh. The workshop helped the research team to overcome engagement challenges in one of the settlements in Andhra Pradesh who were unfamiliar with the research teams’ work and helped familiarise them with the research. These members helped facilitate community engagement for the researchers. Reena Chauhan, Accredited Social Health Activist or ASHA worker works with the community in Eidgah colony. ASHA workers work closely with the communities and link them up with services in the public health facilities. Asha workers used to conduct government-related surveys. “For the first time, someone has asked us anything before conducting any kind of survey. Usually we are just asked about our targets related to our work in taking pregnant women for check ups or checking on newborns, or motivating tuberculosis patients to take their medicines,” said Reena Chauhan, ASHA worker in Shimla Taking feedback from the community is in line with participatory action research methodology which this project is committed to. It also adheres to the principle laid down in the Human Rights Approach to Data, that talks about including means for active, and meaningful participation of relevant stakeholders, especially the most marginalised population groups during the entire data collection process including planning before the survey roll outs. Deciding boundaries of the settlement For the project and particularly for the survey, it was important to determine the boundaries of the settlement- what part of the settlement will be covered for the survey, and what will be left out. The boundaries then determine where the enumerators and researchers 1can move around and conduct the survey. In Vijayawada and Guntur, there were some areas adjoining the informal settlements where the middle class families lived in visibly well-made houses. The project’s Vijayawada-based researcher, Hemanth Chandu sat with community persons, Madhavi, Kosamma, Mahesh and Shiva in RR Peta and Vambay Colony, Vijayawada and Akkamma and Shiva Parvati in Sarada Colony, Guntur. Of these, Madhavi and Shiva Parvati are community