शिमला की बस्तियों में सर्वेक्षण करने का अनुभव

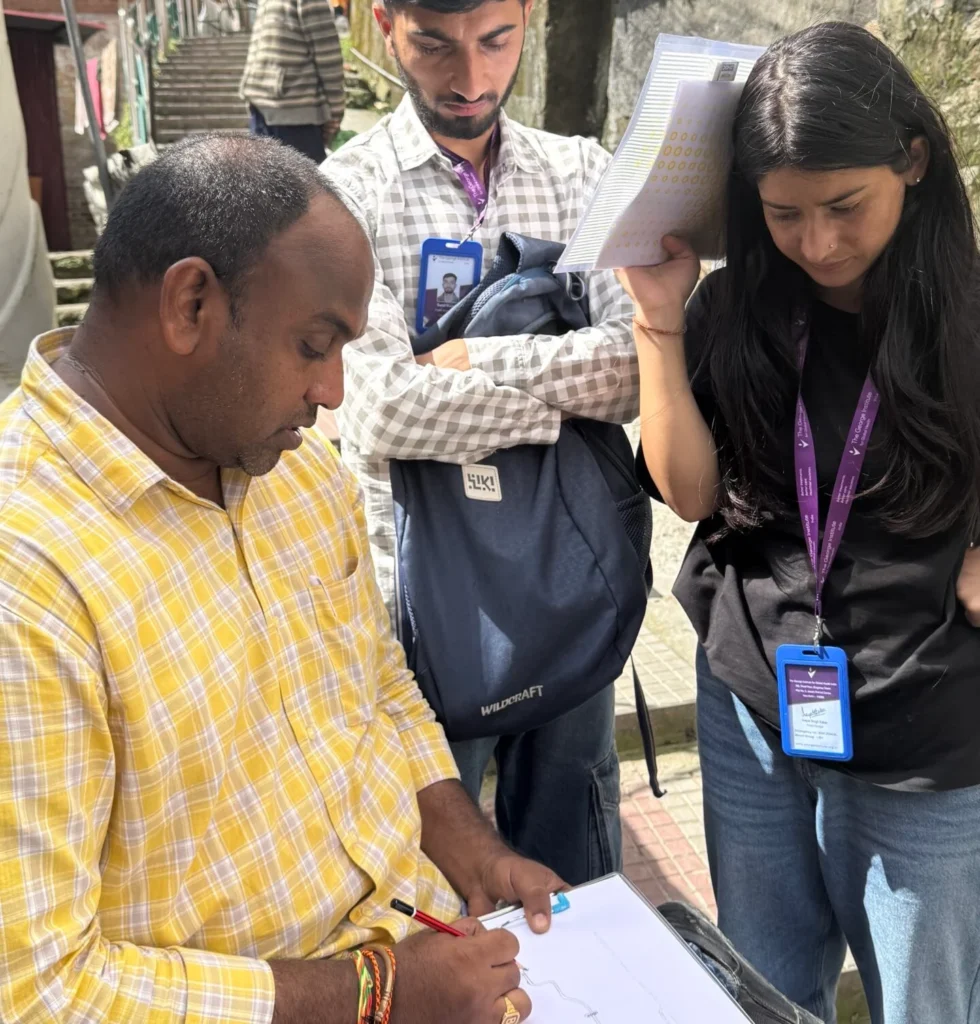

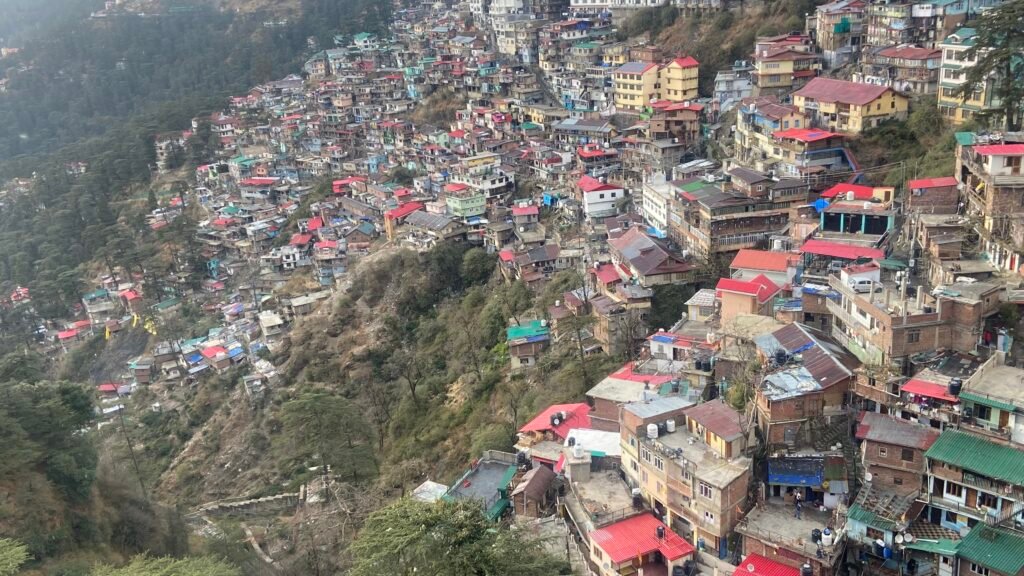

शिमला की बस्तियों में सर्वेक्षण करने का अनुभव साहिल कुमार 2021 में, मैंने अपनी ग्यारहवीं और बारहवीं लाल पानी स्कूल, कृष्णा नगर से की थी। मुझे मेरे घरवालों ने बताया था कि किसी के साथ काम से हटके बात नहीं करनी है, और किसी से लड़ाई झगड़ा नहीं करना है। घर के बड़े मानते हैं कि वहां लोग जल्दी लड़ाई झगड़े में उतर आते हैं, पर मेरे साथ स्कूल के दौरान कभी ऐसी कोई घटना नहीं हुई। सितंबर महीने में जब मैंने Urban SHADE प्रोजेक्ट में काम करना शुरू किया, तभी यही धारणा मेरे मन में थी। मेरी टीम का काम था कि घर-घर जाकर सर्वेक्षण करना। हम पूरे सात लोग ये काम पर लगे थे। इस प्रोजेक्ट में काम शुरू करने के बाद, कृष्णा नगर के लोगों और जगह के बारे में मेरी धारणा और अनुभव में आया बदलाव। हमने Urban SHADE प्रोजेक्ट हिमाचल प्रदेश के शिमला की अनौपचारिक बस्तियों में घरेलू स्तर पर सर्वेक्षण से संबंधित आँकड़े एकत्र करना शुरू किया। हम दो बस्तियों – कृष्णा नगर और ईदगाह कॉलोनी – में काम कर रहे थे। घरेलू सर्वेक्षण का उद्देश्य अनौपचारिक बस्तियों में रहने वाले लोगों के स्वास्थय पर पड़ने वाले प्रभावोंऔर कमज़ोरियों को समझना है। साथ ही चरम मौसम की घटनाओं के दौरान और उसके बाद सार्वजनिक स्वास्थय सुविधाओंमें उपलब्धता को भी समझना है। यह मेरा पहला काम था। मेरा, शुरुआती अनुभव बिल्कुल ना के बराबर था लेकिन पहले ही दिन से नई चीजों को सिखने पर ध्यान दिया। जब पहले दिन हम अपने क्षेत्रों में पूरी टीम के साथ गए तो हमने देखा कि कृष्णा नगर में रास्ते सीधे नही है और बहुत सी सीढ़ियाँ है। यहाँ पर लोगों के घर बहुत पास-पास है, और भारी बारिश के दौरान लोगों के घरो के जल निकासी की स्थिती बहुत खराब है। कृष्णा नगर के लोगों का कहना यही था कि बहुत से लोग आते-जाते है और सर्वे कर के चले जाते है। परंतु कोई हमारे लिए कुछ भी नहीं करता। मैपिंग की समस्याएं हमें ट्रेनिंग के दौरान मैपिंग के बारे में बताया गया। सर्वे के पहले मैपिंग जरूरी थी ताकि कृष्णा नगर की भौगोलिक स्थिति के बारे में और घरों की स्थिति के बारे में अच्छे से पता चले। दोनों क्षेत्र- कृष्णानगर और ईदगाह पहाड़ी क्षेत्र हैं,और रास्तों में उतार चढ़ाव बहुत है। मेरे सीनियर्स और टीम मेंबर्स को भी कृष्णा नगर में मैपिंग के दौरान ऊपर नीचे चढ़के थकान का सामना करना पड़ा। हम सोच में पड़ गए कि यहाँ के लोग, विशेष रूप से बुज़ुर्ग लोग, कैसे रोज चलते फिरते होंगे। सर्वे के दौरान हमें बुज़ुर्ग बताते थे कि उन्हें नीचे से कार्ट रोड पहुँचने में बहुत समय लगता है। बहुत से बुज़ुर्ग डंडा पकड़कर, बीच में बैठ-बैठ कर धीरे-धीरे ऊपर तक पहुँचते हैं। मैपिंग में मुझे कई जरूरी चीजों का ध्यान रखना पड़ता था। कोई घर छूट ना जाए। लोगो से रास्ते को पूछना या कौनसा घर किस से जुड़ा है। कृष्णानगर में पालतू और आवारा कुत्तों का डर बहुत ज्यादा था। हमें डर था कि ये आवारा कुत्ते हमें ही काट न दें। हम लोगों को पूछ कर ही गालियों में जाते थे। जिन घरों में पालतू कुत्ते होते थे वह उन्हें पकड़कर या बांधकर रखते थे। हमने सुरक्षित होकर मैपिंग का काम चालू रखा । मैपिंग में हमें एक ही गली में कई बार आना जाना पड़ता था। शुरुआत में थोड़ी थकान के साथ समय वाला काम लगता था। फिर मुझे इसकी आदत होने लगी। मैंने मैप के चित्र का ज्यादातर काम खुद ही किया है। मैप को पहले मोटे तौर पर बनाया और फिर उसे बड़े चार्ट में लैंडमार्क लिखकर तैयार किया।यह काम मुश्किल था क्योंकि गलीयाँ कहीं न कहीं एक दूसरे से मिलती हैं। इस दौरान, मैं और मेरी टीम घंटों वाल्मीकि मंदिर में बैठकर काम करते थे। वहाँ का माहौल अच्छा था और लोगों को हमारे काम के बारे में जानने में दिलचस्पी थी। मुख्य घरेलू सर्वे की शुरुआत पायलटिंग के दौरान मेरी एक परिवार से बात हुई। इन लोगों ने 2023 में स्लॉटर हाऊस के हादसे को अपनी आंखों से देखा। उन्होने अपने घर के साथ लगती नालियों और बुरी जल निकासी (drainage) के बारे में बताया। उन्होंने बारिश के दौरान अपने घर को छोड़ने की स्थिती और अनुभव को मेरे साथ साझा किया। एक और दुखी परिवार के अनुभव को भी मैने सुना था। उन्होनें कुछ साल पहले नया घर खरीदा था जो कि 2023 के स्लॉटर हाउस क लैंडस्लाइड (landslide) हादसे में तबाह हो गया।आज उस परिवार को किराए के घर में अपना जीवन यापन करना पड़ रहा है। सर्वे के पहले दिनों में मेरा अनुभव ठीक रहा और लोगो से बात करके अच्छा लग रहा था। सर्वे के तीसरे दिन, जब मैं एक आदमी से सर्वे के सवाल पूछ रहा था, उन्होंने घर के संबंधित सवालों के बारे में बुरा मान लिया। उनका व्यवहार मेरे प्रति बहुत अच्छा था परंतु उनको सर्व के कुछ प्रश्नों से थोड़ी परेशानी थी। उन्होंने सर्वे रोकने को कहा और उन्होंने मुझे डेटा टैबलेट से मिटाने को भी कहा। कुछ देर के लिए उन्होंने टैबलेट मेरे हाथ से लेकर उसमें कुछ देखने भी लगे। इसके बाद में हमारे टीम के सीनियर ने कृष्णा नगर के वाल्मीकी मंदिर वहाँ के निवासियों के साथ बैठक की । उन्होंने सर्वे के बारे में अच्छे से समझाया। इस बैठक से लोगों को समाधान मिला और सर्वे सामान्य तरीके से चल पड़ा। और उसके बाद वाल्मिकी सभा के लोगों ने हमें सर्वे के लिए और ज्याया प्रोत्साहित किया। लोगों को दिक्कत व परेशानियाँ लोगो का मेरे प्रति व्यवहार अच्च्छा रहा। लोग जानकारी देने के लिए पूरा समय देते थे और अपने पूर्व प्रभावो को हमारे साथ साझा करते थे। लोग अपनी गंभीर बीमारियों के बारे में भी हमारे साथ जानकारी साझा करते थे। लोगों ने बताया कि कार्ट रोड तक आने-जाने से जोड़ों में दर्द होता है।यहाँ का नाला कूड़े से भरा रहता है, और जो लोग नाले के पास रहते हैं वे इससे ज्यादा परेशान रहते हैं। इससे वर्षा के मौसम में समस्या आती है और बीमारियाँ पैदा होती हैं। कृष्णानगर में ऐबुलेंस की सेवा भी ना के बराबर है। मौसम के कारण