Experiences of co-creating survey with communities facing climate health risks

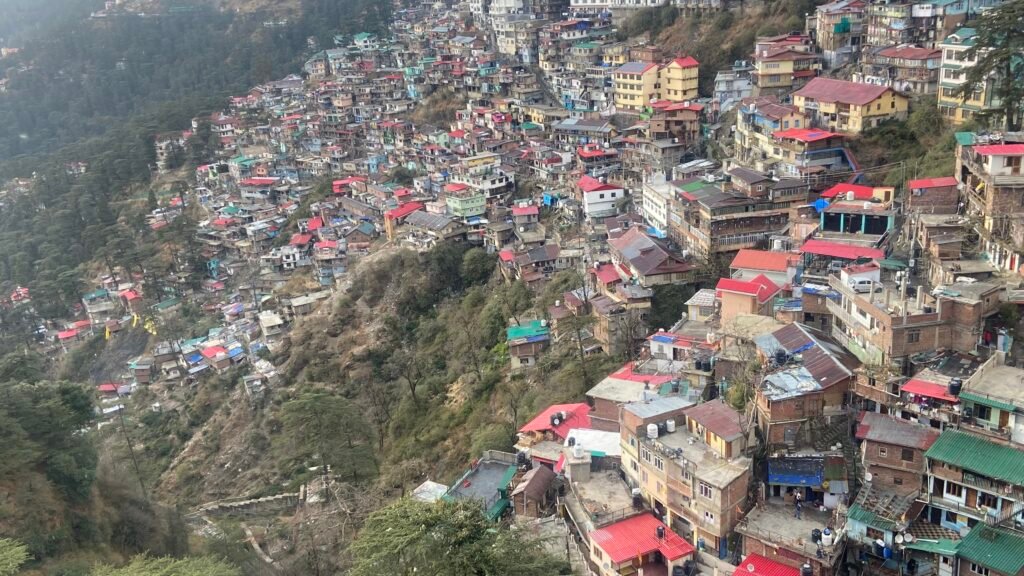

In late October 2025, the Urban SHADE project in India will start on data collection related to the household level survey in the informal settlements in Shimla in Himachal Pradesh, Vijayawada and Guntur in Andhra Pradesh. The household survey aims to understand health impacts and vulnerabilities of people living in informal settlements, as well as the extent of care available to them in public health facilities during and following extreme weather events.

The Urban Shade Project, aims to strengthen health services for people living in urban informal settlements, to respond to impacts of extreme weather events. The enumerators in both states underwent an extensive training programme in September, which covered the details about the project, ethics of data collection, mapping and use of survey software. The project has involved the community in every step of the way.

The design of the survey tool – Household Survey: Social and Health Vulnerability Assessment related to Extreme Weather Events– was led by a member of the research team, Malini Aisola with extensive inputs from research and field team members. The survey includes social demographic profiles of household members, access to utilities and infrastructure, access to health services, housing, past impact of extreme weather events, people’s perceptions, awareness and responses on extreme weather events. The survey will be conducted in informal settlements in Vijaywada-Guntur, and two informal settlements in Shimla.

The two extreme weather events we are looking at in the project are extreme heat and extreme rainfall/flooding.Through the household survey, the team aims to generate context-specific data about a variety of indicators of social and health vulnerability, and provide insights about how they shape experiences of extreme weather events. For example, those living in the poor quality houses, and do informal work may feel the impact of extreme heat more.The survey would enable granular descriptions at the settlement-level of prevailing conditions that could inform government policies and local preparedness planning including provision of health services.

Consulting the community on survey tool

The Urban SHADE research teams had fortunately worked with some of the settlement sites in the project earlier in another project called Accountability for Informal Urban Equity (ARISE), an action research project focussing on health and wellbeing of sanitation workers.

In some other communities, efforts were made to engage with the community in a meaningful way before data collection. In Eidgah colony, a public meeting was organised with support from key stakeholders including the Maulvi of the mosque, the ward councillor, community leaders, an official from National Health Mission and ASHA workers in the settlement.

Anmol Somanchi, a developmental economist and member of the research team in an advisory capacity, helped the team develop a conceptual framework for measuring vulnerabilities. After developing a basic draft with inputs from research and field team members, our team presented it to the members and stakeholders of the settlements in Vijayawada, Guntur and Shimla.

The workshops included residents, community leaders, elected officials, health workers, civil society members of these settlements we are studying in including Krishna Nagar, and Eidgah colony in Shimla, Vambay colony and New Raja Rajeswari Peta (also called RR Peta) in Vijaywada, and Sarada colony in Guntur. The one-day workshop was organised by the research team of Inayat Singh Kakar and Yetika Dolker in Shimla, and Pavani Pendyala and Hemanth Chandu in Vijayawada in May.

Apart from talking about the survey, key questions were read out and displayed in the workshop to the community members to discuss their relevance, the way they are worded, as well how the data could be relevant to the community for advocacy. Community members gave suggestions on improving the questions as options to click to elicit an appropriate answer.

Mahesh aka Shiva who lives in RR Peta gave suggestions to simplify the Telugu questions, making it closer to spoken language rather than very Sanskritised. “In the workshop, you (Urban SHADE team) asked us whether we were able to understand the language or not, and modified the questionnaire based on the language we were able to understand,” said Mahesh.

The workshop helped the research team to overcome engagement challenges in one of the settlements in Andhra Pradesh who were unfamiliar with the research teams’ work and helped familiarise them with the research. These members helped facilitate community engagement for the researchers.

Reena Chauhan, Accredited Social Health Activist or ASHA worker works with the community in Eidgah colony. ASHA workers work closely with the communities and link them up with services in the public health facilities. Asha workers used to conduct government-related surveys.

“For the first time, someone has asked us anything before conducting any kind of survey. Usually we are just asked about our targets related to our work in taking pregnant women for check ups or checking on newborns, or motivating tuberculosis patients to take their medicines,” said Reena Chauhan, ASHA worker in Shimla

Taking feedback from the community is in line with participatory action research methodology which this project is committed to. It also adheres to the principle laid down in the Human Rights Approach to Data, that talks about including means for active, and meaningful participation of relevant stakeholders, especially the most marginalised population groups during the entire data collection process including planning before the survey roll outs.

Deciding boundaries of the settlement

For the project and particularly for the survey, it was important to determine the boundaries of the settlement- what part of the settlement will be covered for the survey, and what will be left out. The boundaries then determine where the enumerators and researchers 1can move around and conduct the survey.

In Vijayawada and Guntur, there were some areas adjoining the informal settlements where the middle class families lived in visibly well-made houses. The project’s Vijayawada-based researcher, Hemanth Chandu sat with community persons, Madhavi, Kosamma, Mahesh and Shiva in RR Peta and Vambay Colony, Vijayawada and Akkamma and Shiva Parvati in Sarada Colony, Guntur. Of these, Madhavi and Shiva Parvati are community researchers with the Urban Shade Project. Chandu explained the definition of an informal settlement, and they discussed what parts of the settlement is informal according to them.

“It was basically the community who decided what the boundaries of the settlement should be for the project. They had the knowledge as they have been walking around the settlements for years,” said Hemant Chandu, Urban SHADE researcher in Andhra Pradesh

In Shimla, the research team reached out to community members, officials from the Municipal Corporation and ASHA workers of both settlements to determine the boundaries of the settlements, said Dolker.

As per the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), an informal settlement refers to urban settlements or neighbourhoods that are developed outside the formal system. It means that they either do not have land ownership and tenure, or do not meet a range of regulations relating to planning and land use, built structure, health and safety.

Mapping the settlement

The India research team hired seven enumerators for the Shimla survey, and nine enumerators for the Vijayawada and Guntur survey. A five-day workshop was held in Vijayawada and Shimla before the survey work began.

A significant portion of the workshop with enumerators had to do with ethics of data collection. The Project is cognisant of the ethics involved when it comes to collecting data from vulnerable communities who live in informal settlements. Many of the persons living in informal settlements are from historically discriminated oppressed castes, people belonging to nomadic and denotified tribes erstwhile labelled “criminal tribes” during the colonial rule, and those from stigmatised professions such as waste picking and sanitation work.

The enumerators were trained not just to understand the objectives of the survey and the methodology, but also the ethics of data collection. They were trained with examples on how gender and cultural norms should be respected, as well as the fact that data collection should not reinforce any existing discrimination, bias or stereotypes faced by the people.

The enumerators learned the mapping exercise with Balajirao Nemala, Project Manager with The George Institute, handling several trials all over India. The survey process involves mapping, which means literally drawing a map on paper on the settlement. Nemala trained enumerators to go out in the informal settlements and draw each lane and alleyway and building structures on a map, helping them guide them through the area with ease while conducting the survey.

While the enumerators were making the map, many residents asked the enumerators and the researchers about what they were doing, and about the survey. The enumerators were transparent in their communication and explained the project in detail that satisfied the community members.

The enumerators and researchers in Shimla got help from particularly two residents of Krishna Nagar -Puneet and Rahul. They helped make sense of the vast topography of the settlement and divide it into zones making it easier for enumerators to move around the settlement and ensure no overlaps

These maps can now be used by the community members and the state to understand the length and breadth of the informal settlement geographically and provide updated information on the number of households within the settlement which can enable local planning.

Community involvement in the survey

The involvement of community was evident in the use of community spaces. In Shimla’s Krishna Nagar, after seeking permission from the residents, the enumerators sat in the Valmiki Mandir and finalised the maps. This also enabled interactions and engagement with community members visiting the temple and allowed the research team to explain the purpose of the activities being conducted.

After making maps, the enumerators had to put numbered stickers on each household, to help sampling and identifying households to be included in the survey. The research team is ably supported by Aman Rastogi, Biostatistician at The George Institute for Global Health in creating the sampling strategy and calculating the sample size.

In Krishnanagar, Shimla where community members have been struggling for ownership and land rights, people perceive a threat of eviction from the settlement. Mapping of buildings creates a fear about the purposes for which the data may be deployed. Relying on relationships of trust built during the ARISE project, the research team received support from community members to dispel fears and apprehensions raised by some community members.

“During the mapping activity, community members have been helping vouch for us to others who had questions such as why we are creating maps and why we are putting stickers on some houses. They are also helping spread the word and assure others to participate in the survey,” said Kakar, who works out of Shimla.

In both Shimla and Vijayawada, local elected leaders were informed about the project and the survey, with them giving written permissions as well in Vijayawada. In Shimla’s Eidgah colony, the religious leader, Maulviji as he is called, promised to make announcements related to the survey from the loudspeakers during the Friday Prayers.

The survey will begin in this month, and aims to fill the gap in data related to social and health vulnerabilities of the poor in the context of extreme weather events. It aims to provide information related to socio-economic factors that affect risks of extreme weather events, availability and accessibility of health services, impacts of previous extreme weather events, and perceptions of communities about extreme weather events and coping strategies.

Findings from the data collected will be taken back to community members and leaders who will be involved in creating evidence- based interventions to strengthen health services, in partnership with the health departments of respective state governments. Research teams will also work with community members and leaders to disseminate findings to local and state governments.