How terrain of the informal settlement has an impact on health

Almenatu Samura

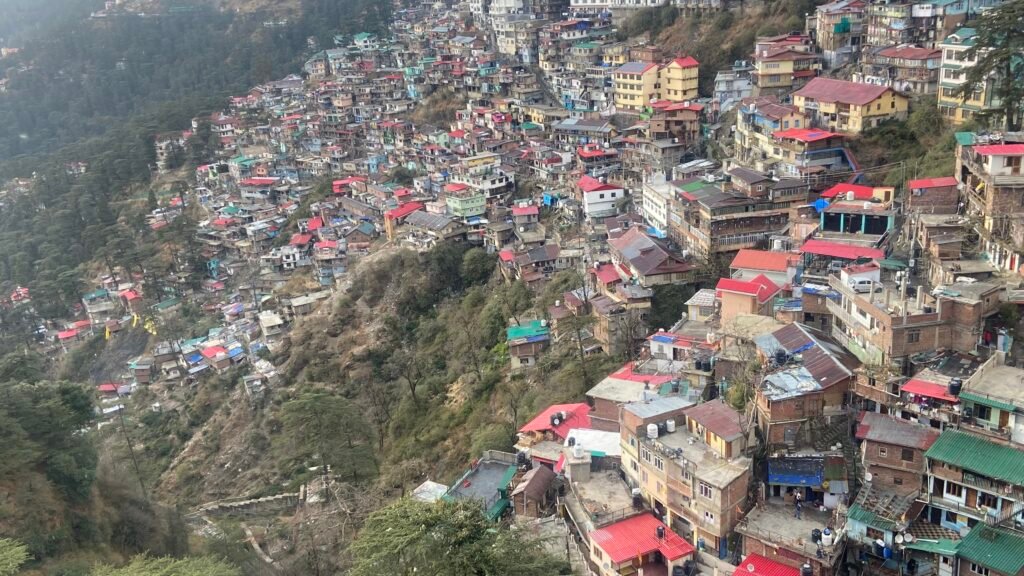

It is well known that living in informal settlements poses a risk to health because of lack of formal recognition, and the residents facing various socioeconomic, environmental and political exclusions. In the coastal informal settlement of Susan’s Bay, one’s access to health is also determined by what part of the settlement she lives in.

Since the settlement is built on steep, tiered landscape, people living in the lower parts of the settlement have to climb long flights of uneven stairs to get anywhere. This includes going to the only public health facility, Susan’s Bay Community Health Centre that serves the settlement, which is perched on the upper end of the informal settlement.

While this reality touches every resident, it falls heaviest on the most vulnerable groups persons with disabilities, the elderly, children, and especially pregnant women.

The terrain makes daily movement for residents, especially vulnerable ones, exhausting and sometimes impossible. “There’s no part of the community without staircases. To exit the area, you must climb, which is a major challenge for us,” one resident explained.

Residents at the lower end of the settlement struggle to reach it, especially during medical emergencies, and disasters such as fire and storms. In 2021, a massive fire swept in Susan’s Bay injuring hundreds of people and destroying much of the infrastructure. The lack of roads prevented fire engines to reach the community to put out the fire.

Life-threatening delays during childbirth

Pregnant women find the uphill journey daunting, often missing critical antenatal appointments or experience life-threatening delays to reach the health facility during labour. The consequences are devastating from miscarriages and preventable complications to tragic maternal and newborn deaths.

The community members talk about cases where pregnant women have failed to reach health centre, losing their lives.

As per the latest UN estimates, Sierra Leone has made strides in reducing the maternal mortality ratio from 1682 deaths per 100,000 live births in 2000 to 354 in 2023. But 354 deaths per 100,000 live births is still too high a number- about three maternal deaths a day.

Stories of women dying of childbirth abound in the settlement.

A community leader speaks about the case of a pregnant woman who died of childbirth after she could not reach the health centre. She lived in the lower end of the informal settlement.

“The pregnant woman was unable to reach the health center. She returned home and delivered with a traditional birth attendant (TBA). The mother couldn’t make it out alive,” recalled a community leader. After the complications, the woman was taken to the health facility where an emergency C- section was done.

Beyond the steep terrain, narrow and congested roads compound the crisis. Traders often line the pathways, leaving little space for movement. The environment is physically inaccessible, disaster-prone, and socially excluding. This is especially true when a fire breaks out, or during floods when it is impossible to move fast. A disabled resident said that being carried on someone’s back is “dehumanising.”

No “free” healthcare

There are other barriers to access to healthcare. Despite the Free Health Care Initiative (FHCI) that was launched in 2010, people talk about hidden costs, medicine shortages. Informal payments keep many away from clinics.

Many residents living in Susan’s Bay lack reliable income and the rising cost of living is deepening their hardship. This hardship is compounded for vulnerable populations who then depend on informal health care rather than the formal system.

“I don’t have a steady job, so if I can’t afford tests or drugs, I simply go without treatment,” said a man with a disability.

A recent Human Rights Watch report looking at obstetric violence in Sierra Leone said that indigent women are at a higher risk of obstetric violence if they cannot make informal cash payments to staff in government facilities for services, drugs, and other commodities, even if in an obstetric emergency. The report is based on more than 130 interviews with patients, healthcare providers, government officials, and public health and policy experts in Sierra Leone in 2024 and 2025.

Community health workers say that many pregnant women too are abandoned by their partners, left to fend for themselves. Accessing formal healthcare becomes daunting for such women.

In the face of these barriers, community health workers (CHWs) serve as the invisible bridge between the health system and those most at risk. They identify pregnant women who have not registered for antenatal care, provide referrals, and raise awareness on safe delivery practices.

“Some women never attend ante-natal until CHWs visit them at home. Many don’t even have antenatal cards,” said a CHW.

Without their outreach, maternal and newborn deaths in Susan’s Bay would likely be far higher.

Susan’s Bay’s story is not an isolated one. Across Sierra Leone’s informal settlements, residents find it difficult to access healthcare. Addressing this requires more than infrastructure; it demands inclusion, empathy, and sustained attention. To build resilience in Susan’s Bay, interventions must prioritise accessible and inclusive healthcare facilities, improved mobility pathways for persons with disabilities and the elderly, community-based maternal health programs, livelihood support for vulnerable women and people with disabilities, and stronger emergency preparedness and response systems.